Child labour in global supply chains

A milestone in the global fight against child labour was recently achieved by the Dutch government with the ratification of a new child labour due diligence law. This law requires all companies selling products or delivering services in the Netherlands to undertake due diligence measures to prevent child labour in their supply chains.

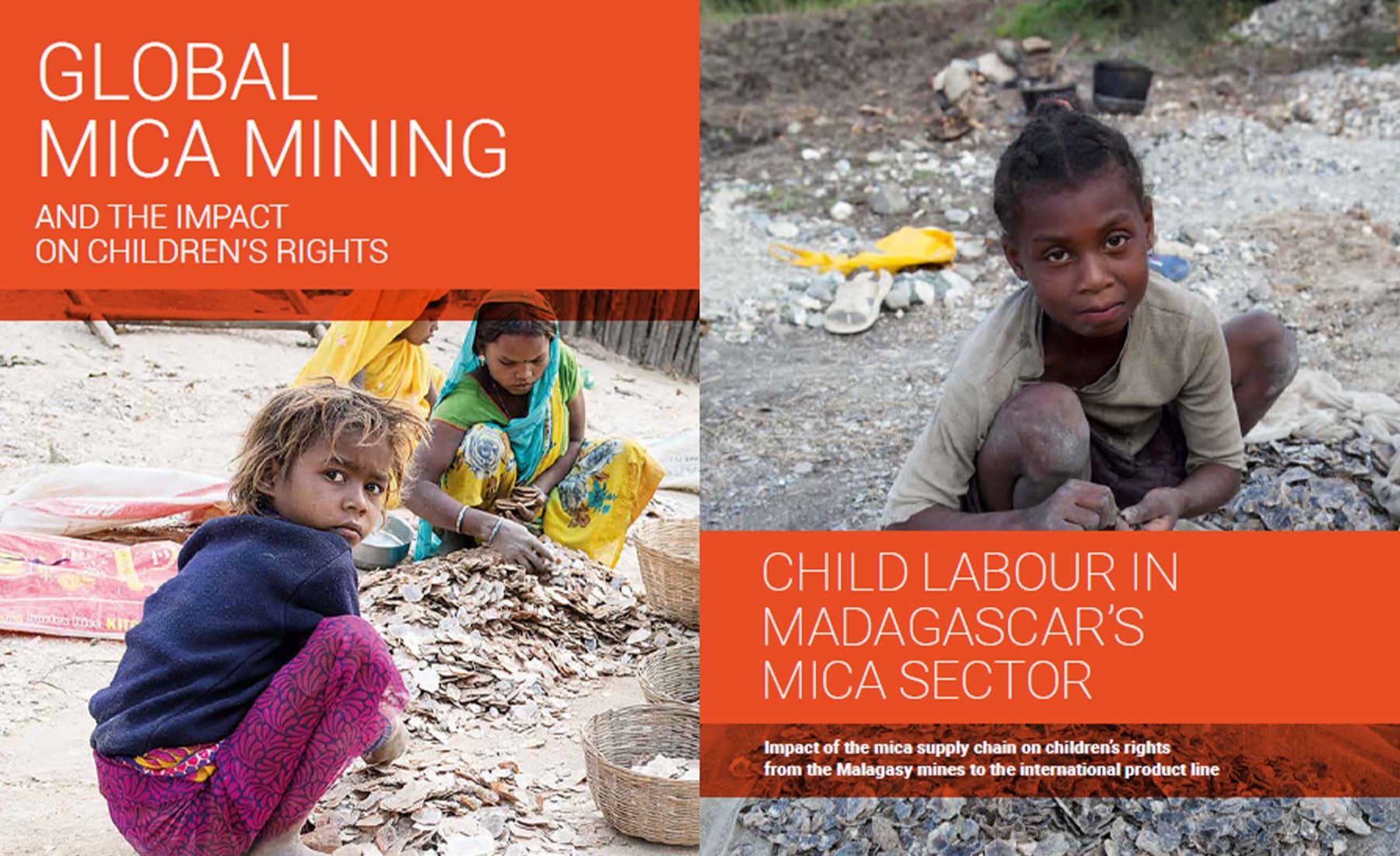

Whilst there have been great developments in recent years in the way that businesses engage with child labour, an estimated 152 million children remain in child labour globally. But statistics such as these often feel too large and difficult to connect with. What this means, practically speaking, is that there is a high likelihood that child labour is occurring in many companies’ supply chains.

A personal view: Luke Smitham talks about his experiences in the fashion and textiles sector

“The first time I came across child labour was during garment factory visits in Myanmar. The sites were producing for well-known British and European retail brands. The brands had no idea; they had well-publicised child labour policies and the sites had recently passed audits against their standards.

We spoke to the factory managers who were honest and open, and certainly not malicious. They felt hiring children was essential, even if they were less efficient, more distracted and less reliable than adult workers. The region was poor, there were no schools available and the government didn’t care. They felt that at least in the factory the children were safe (even though any work within a factory where there is machinery is considered hazardous for children) and not on the street. In fact, some managers even felt it was a community service – children’s wages were supporting families and allowing communities to survive in difficult circumstances.

Ultimately these factories moved away from hiring children, through changing manager mindsets and brand pressure. However, these are only a tiny fraction of the children currently working in hazardous conditions.”

Factors that increase child labour risks

As Luke’s experience shows, child labour is a complex issue and there are no one-size-fits-all solutions. Nevertheless, there are certain factors that are known to increase the likelihood of child labour occurring:

Poverty: families may rely on a child’s income to increase the household income, exacerbated if the parents are receiving no pay, low wages, or late payments for their own labour.

Subcontracting: this reduces visibility into labour standards within a company’s supply chain and consequently increases the risk of child labour. Subcontracting home-based labourers particularly increases the risks and is common in garment supply chains.

Poor access to education: those not in school are more likely to end up helping their parents with their work. Minority groups are most likely to be excluded from accessing schooling.

Informal employment: risks of child labour are higher amongst informal workers

Companies’ impact on off-site child labour

Moving beyond children working IN global supply chains, companies need to recognise how their activities encourage child labour AROUND their core business activities. For example, there may be children working on the peripheries in domestic work or prostitution, or even acting as teaboys or girls on hazardous work sites.

Furthermore, since child labour is a systemic issue, a company may eliminate the issue on their sites of operation but that does not necessarily eliminate child labour altogether. Children removed from one site may move into other, sometimes more vulnerable forms of labour or clandestine activities. Therefore, if companies find children in their supply chain, they should be ready to support, manage and fund the remediation process, and avoid simply pushing the problem into a darker corner.

Strategies for success

There are a multitude of reasons why child labour exists today, but these complexities are no reason for inaction. There are key steps that companies are recommended to take, for example as set out in due diligence guidance developed by the OECD:

- Make a clear policy commitment to not tolerate child labour (as defined by ILO Conventions) in the company’s own operations or at any point in the supply chain.

- Identify potential risks. Seek to understand the local cultural and political context of the company’s operations and supply chain. For example, are there particular socio-economic or cultural factors in parts of the supply chain that may increase the likelihood of child labour? Involve workers in supplier assessments.

- Take action to prevent any immediate and critical risks that are identified, and develop longer-term solutions to mitigate the risks. This will likely include awareness raising and capacity building.

- Listen to the community, and to the children. Grievance mechanisms should be accessible, transparent, and dialogue-based.

- Monitor and evaluate impact. This will ensure that actions are having the desired effect and will allow you to learn what has worked and what has not.

- Recognise the need for partnership in sustainably ending child labour. These partnerships may range from governments and multilateral organisations, to NGOs and local community groups.

The Dutch regulation on child labour is the latest example of a compliance requirement for companies, but it is unlikely to be the last. Companies need to ensure they have a clear understanding of whether this is a risk in their supply chains; the introduction of the Dutch regulation now raises the urgency of doing so for many companies.

Kumi has significant experience working with companies to manage, monitor, and mitigate issues such as child labour in supply chains. If you’d like to know more about due diligence compliance and how Kumi can help you, please contact us.