OECD due diligence: implications for large-scale mining

The OECD’s Due Diligence Guidance has been the cornerstone standard for responsible sourcing efforts in the metals and minerals sector since its publication in 2011. However, many industry stakeholders have long assumed that the Guidance was only applicable to supply chains of tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold, or that it was mainly relevant to supply chains from central Africa where there was an active presence of artisanal and small-scale (ASM) mining. Such assumptions are misplaced.

The responsible sourcing compliance requirements recently introduced by the London Metal Exchange (LME) mean that producers of industrial metals such as aluminium, copper, cobalt, lead, nickel and zinc need to understand what the implications of the standards set out in the OECD Guidance are for their operations and be prepared to demonstrate that they comply with these standards.

This is likely to have implications even for those producers that do not trade on the LME. Based on experience from other markets, we expect that growing awareness will lead to both downstream customers and trade financiers increasingly seeing the LME’s requirements as a ‘hygiene factor’; a minimum compliance standard for mitigating potential exposure to responsible sourcing risks. Due diligence that is aligned with the OECD Guidance is already a performance expectation within the ICMM’s Mining Principles, which the 27 large-scale mining companies that are ICMM members are committed to uphold. Growing numbers of mining industry initiatives or certification schemes are seeking to align their requirements with the OECD’s recommendations or have stated their intention to do so. These cover metals including aluminium, cobalt, copper, lead, nickel and zinc.

So, what does this mean in practice? What are the implications for large-scale mining producers and for companies that purchase minerals and metals from large-scale miners?

Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (CAHRAs)

The starting point for the applicability of the OECD Guidance is whether minerals or metals may originate from a conflict-affected and high-risk area (CAHRA) or be otherwise linked to conflict or serious abuses due to the mineral supplier’s circumstances.

The definition of CAHRAs is often substantially misunderstood. A common mistake we see in our work at Kumi is companies taking a very narrow interpretation of what ‘high-risk’ means. Often the emphasis is given to ‘conflict’ only, whereas serious abuses relating to governance or human rights are equally important risk factors. CAHRAs can be defined by the presence of risks relating to conflict, human rights abuses, poor governance and mineral flows (smuggling). A ‘trigger’ on any one of these risk factors is sufficient to identify a CAHRA.

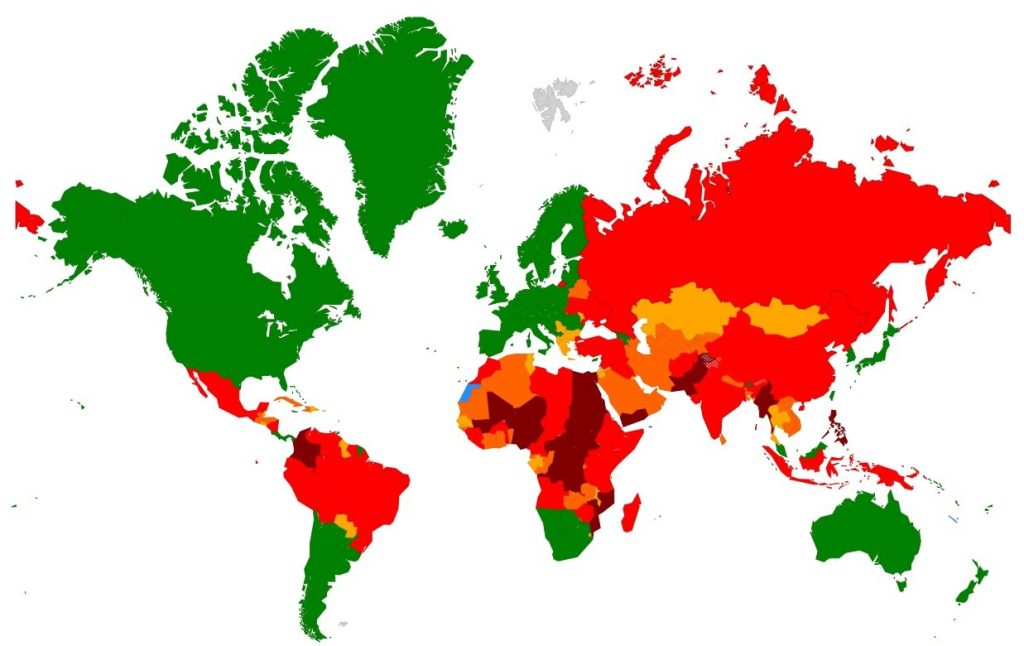

As can be seen below, when the four CAHRA risk triggers are taken into account, this becomes a broad starting point due to the need to consider multiple different risk factors. At Kumi we have developed a tool called CAHRA Map to support companies in identifying where they should focus their due diligence efforts. The image below shows an example of how our data visualisation tool identifies all the countries where one or more CAHRA triggers (conflict, human rights, governance or mineral flows) has been identified, based on Kumi’s analysis of highly credible, published risk data and indices. Many of these countries are significant mineral producers.

Whilst the identification of a CAHRA does not necessarily mean that all producers within that CAHRA are themselves high risk, it does mean that purchasers of minerals originating from (or transiting through) that CAHRA need to do further mining supply chain due diligence as the location of the producers’ operations have increased the possibility of certain risks being present.

Large-scale mining companies operating in these countries need to ensure they can demonstrate that their operations are aligned with the standards set out in the OECD Guidance, with a particular focus on those risks that have been identified by the OECD and other stakeholders as being especially relevant to large-scale mining.

Corruption risks

The OECD Guidance expects companies to commit to avoiding bribery and not to misrepresent taxes, fees and royalties paid to governments for the purposes of mineral extraction.

Many mining companies operate in jurisdictions where governance is weak and therefore risks relating to corruption are high. Over 250 mining industry participants who were surveyed by EY identified bribery and corruption as one of the top ten risks facing the sector in 2019-20. There are numerous examples of legal action being taken against mining companies for bribery and corruption issues.

The fact that a mining company may be a large multinational, perhaps also publicly listed, is not enough on its own to provide confidence that it complies with the standards set out by the OECD. Companies are expected to have clear corporate commitments, to undertake risk-based due diligence on suppliers and business partners, and to be transparent about the taxes, fees and royalty payments. This includes transparency on payments made to secure access to mining concessions.

Mining companies, particularly those operating in higher risk jurisdictions, need to be prepared to provide this information to their customers. Mineral purchasers and financial institutions need to ensure the scope of their mining supply chain due diligence adequately addresses these issues.

Security forces & human rights

Risks relating to mine security forces have prominent coverage in the OECD Guidance, and with good reason. There a many examples of mine security forces being implicated in human rights abuses, with just one recent example being the case of the North Mara gold mine in Tanzania. The risks that security forces may commit human rights abuses are increased in jurisdictions where the rule of law is weak and the rights of workers and civil liberties are not always protected.

Under the OECD Guidance, mining companies are expected to apply the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights (VPs) when contracting security forces. The VPs were launched twenty years ago specifically in response to the recognition by governments, industry and civil society that security forces were frequently being implicated in human rights abuses. However, Kumi’s experience is that in the field, the site-based management of many mining operations have still not heard of the VPs.

Mining companies need to ensure that effective controls are in place to implement the standards and practices set out by the VPs across their operations, including joint-ventures and major contractors employing their own security forces. Mineral purchasers and financial institutions need to ensure that their human rights due diligence adequately challenges the controls that mining companies in their supply chain have established to implement the standards set out in the VPs.

Linkages to small-scale mining

It is important not to stigmatise artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM). On the other hand, it is also an incontrovertible fact that certain risk factors, such as the potential for child labour or for mineral production to be appropriated by armed groups, may be more likely in ASM supply chains than in industrialised mining operations. The vulnerability of many ASM communities is a key factor elevating this risk. For example, it has been widely reported that drug cartels in Colombia make more money from controlling gold mining than they do from cocaine.

It is important to consider that the term ‘ASM’ covers a broad range of types of operations; the ‘small-scale’ part of ‘artisanal and small-scale mining’ is often overlooked. Small-scale mining is usually undertaken by legal mining operators who have access to some level of mechanisation, for example a backhoe and perhaps a concentrator plant.

Also often overlooked is the fact that many of these small-scale operations supply their ore or concentrates to large-scale mine and smelter operators. This is true across many geographies and mineral types. Large-scale mining companies can be connected to these small-scale operations both directly, for example by purchasing ore or concentrates from third party producers, or indirectly through joint venture relationships or off-take or tolling agreements with other companies that themselves source from small-scale operations. Either way, under the OECD Guidance, large-scale mining companies would be expected to undertake due diligence on third party ore producers.

Linkages between large-scale and small-scale mining are more likely in geographies where there is an active ASM sector. Large-scale mining companies operating in a country where there is a significant ASM presence are not necessarily connected to that ASM activity in any way. Nonetheless, it is important that mining companies are honest about the linkages that do exist, undertake due diligence on such linkages and ensure relevant risks are responsibly mitigated. In any event, large-scale mining companies are encouraged to act responsibly and sensitively in any interactions they may have with ASM communities. Equally, mineral purchasers and financial institutions should not be naïve about the potential for linkages between large-scale and small-scale mining and ensure that their due diligence adequately addresses such risks.

–

If you would like to learn more about how Kumi can support you with human rights due diligence and responsible sourcing, please contact us. For more information on Kumi’s CAHRA Map, please visit: www.cahramap.com